The Command Line#

In this chapter, you’ll meet the command line and learn how to use it. Beyond a few key commands like pip install <packagename>, conda activate <environmentname>, and jupyter lab, you don’t strictly need to know how to use the command line to follow the rest of this book. However, even a tiny bit of knowledge of the command line goes a long way in coding and will serve you well.

To try out any of the commands in this chapter on your machine, you can select ‘New Terminal’ from the menu bar in Visual Studio Code (Mac and Linux), use the Windows Subsystem for Linux or git bash (Windows), or use a free online terminal such as WebVM or tutorials point.

This chapter has benefited from numerous sources, including absolutely excellent notes by Grant McDermott, Melanie Walsh’s Introduction to Cultural Analytics & Python, Data Science Bootstrap, calmcode.io, and Research Software Engineering with Python. A promising resource that, at the time of writing, was still being compiled is Data Science at the Command Line.

What is the command line?#

The command line is a way to directly issue text-based commands to a computer one line at a time (as distinct from a graphical user interface, or GUI, that you navigate with a mouse). It goes under many names: shell, bash, terminal, CLI, and command line. These are actually different things but most people tend to use them to mean the same thing most of the time. The shell is the part of an operating system that you interact with but mostly people use shell to mean the command line. bash is the programming language that is used in the command line; it’s actually a synonym for ‘Born Again SHell’. The terminal is sometimes used to refer to the command line on Macs. Finally, a CLI is just an acronym for command line interface, and is often used in the context of an application; for example, pip has a command line interface because you run it on the command line to install packages (pip install packagename).

It’s worth mentioning that there’s a big difference between the command line on UNIX based systems (MacOS and Linux), and on Windows systems. Here, we’ll only address the UNIX version. There is a command line on Windows but it’s not widely used for coding. If you’re on a Windows machine, you can access a UNIX command line using the Windows Subsystem for Linux.

Why is the command line useful?#

The command line has many uses. Graphical user interfaces are, generally, a bit easier to use but they’re not very repeatable or scalable. Because the command line uses text-based instructions and can be programmed, it is both repeatable and scalable; properties that are very useful for research and analysis.

The broad reasons you might use the command line to issue instructions include:

software functionality: some software only has a command line interface

efficiency: your computer has limited memory, which graphical user interfaces use a lot of—the command line uses less

reproducibility: scripts that run on the command line are reproducible in a way that clicking around a graphical user interface is not

hardware functionality: for high-performance and cloud computing the command line is often the only game in town

automation: multiple programmes, with inputs and outputs, can be run in sequence from a script launched in the command line

Here are some specific tasks you might use the command line to complete:

keep your code under version control

renaming and moving multiple files in one command

finding files on the computer

transforming between document types, for example \(\LaTeX\) (.tex) to Word (.docx)

connecting to, and using, cloud resources

Using the command line#

Bash is often the default command line shell on UNIX but zsh has gained popularity and is now the default for Mac. If you’re wondering what to use then I recommend zsh (Z Shell) from oh-my-zsh.

To open up the command line within Visual Studio Code, you can use the ⌃ + ` keyboard shortcut (on Mac) or ctrl + ` (Windows/Linux), or click “View > Terminal”.

You should now see something like this

username@hostname:~$

Let’s break down what this is telling us. username says who the current user is; @hostname denotes the name of the computer; ~ is the default (home) directory; and $ is the ‘command prompt’, a signifier that this is where you should type your command. (Note that this line may look different depending on what shell and/or operating system you’re using.)

Let’s try a simple command: type date into a command line window and hit return. You should see today’s date and time (and timezone). You could also try echo hello and whoami.

All commands that you run in the terminal have the same structure:

command, followed by option(s), followed by argument(s). The options are also called flags. An example serves to demonstrate this: if you have a terminal open in a directory that includes a CSV file called ‘data.csv’, the command to look at the first 5 lines is:

head -n 5 data.csv

here head is the command that looks at the start of the file, -n is an option, 5 is the argument to get 5 lines of the file, and data.csv is the final argument-the file name.

The flags or options, such as -n in the example above, typically begin with a dash (-) or, occasionally, a double dash (--). They can also be chained together, for example ls -la combines ls -a and ls -l.

Warning

Spaces take on a special role when using the command line. For this reason, it’s good practice to avoid spaces in file names. If you need to refer to a filename with spaces in, you’ll need to use quotes or escape the spaces in the file names using a \, for example this is my file.txt becomes this\ is\ my\ file.txt

To run programmes from the command line, all you need is the name of the programme as the command: in fact, commands are programmes. The date command refers to an actual programme on your computer that you can find. And this also explains a bit of what’s going on when you run a script from the command line (more on that later).

Once you’ve run a few commands, you’ll notice that you can’t navigate around the command line like you can a text file or Python script. Here are some tips for navigating the command line:

use tab to complete commands you’ve only partially written out. Try it by typing

datthen hitting tab.use the ↑ and ↓ keys to scroll through previous commands.

to skip whole words, use ⌥ + → and ⌥ + ← on Mac, or ctrl + → and ctrl + ← on Windows and Linux.

ctrl + a to move the cursor to the beginning of the line.

ctrl + e moves the cursor to the end of the line.

ctrl + k to delete everything to the right of the cursor.

ctrl + u to delete everything to the left of the cursor.

ctrl + r to search through previously used commands

Using Python on the command line#

There are several ways in which the command line is useful for Python (and these ways are applicable to other languages too).

Of course, packages are installed at the command line, for example to install Jupyter Lab (for running notebooks), the command is

uv add jupyterlab

Say you have a script called analysis.py, you can run it with Python on the command line using

uv run python analysis.py

which calls Python as a programme and gives it analysis.py as the argument.

Jupyter Notebooks are also run from the command line. If you have Jupyter Lab installed, you can start a notebook server with

uv run jupyter lab

Useful commands for the terminal#

Now we’ll see some useful commands for the terminal.

Command |

What it does |

|---|---|

|

Shows a manual for the given command |

|

Creates an empty file named |

|

Open a file in VS Code (creating it, if it does not exist) |

|

creates a new folder called |

|

Prints |

|

Print the full contents of |

|

Print the start of a file |

|

Print the end of a file |

|

Redirects output from screen to |

|

Redirects output from screen to the end of |

` |

` |

|

Print out the contents of a file in paginated form. Use |

|

Returns number of lines in input, for example |

|

Arrange lines in a file in alphabetical order |

|

Remove duplicate lines from input, for example |

|

Move or rename a file; for example, |

|

Copy a file; for example, |

|

Permanently remove a file |

|

Permanently remove an empty directory |

|

⚠ Permanently remove everything in a directory ⚠ |

|

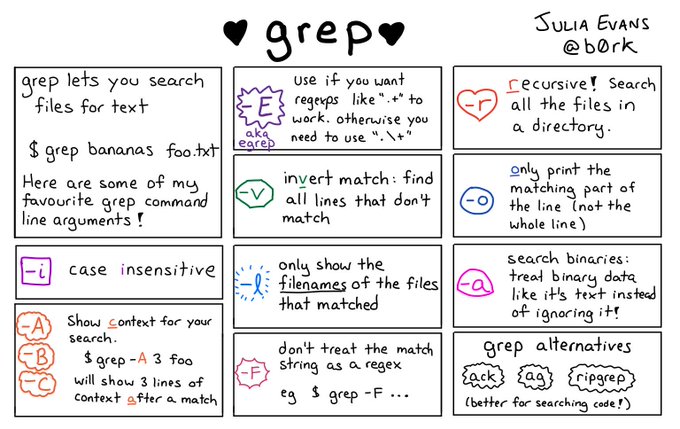

Search for a given term, for example |

|

Basically, this means list stuff (files and folders) in the current directory |

|

List stuff in the current directory even if it’s hidden |

|

List stuff in a more readable format and show permissions |

|

List stuff by size |

|

Give information on the file type of |

|

Find specific files on your computer, can be piped into other commands for example |

|

Show a single summary of the differences between two files. |

You can write for loops in bash (remember, it’s a language). The general structure is

for i in LIST

do

OPERATION $i # the $ sign indicates a variable in bash

done

These can be squeezed into a single line (though it’s less readable):

for i in {1..5}; do echo $i; done

A more interesting example is giving the number of lines of text, number of words, and number of characters of every CSV file in a directory:

for i in $(ls *.csv)

do

wc $i

done

We can get even more fancy with the above example and put those counts in a new text file:

touch counts_of_csvs.txt

for i in $(ls *.csv)

do

wc $i >> counts_of_csvs.txt

done

A couple of new features appeared in the examples above.

* is a wildcard character, it tells bash to look for anything that ends in “.csv”. This is not the only special case; ? serves a similar purpose of standing in for any character but just one character rather than arbitrarily many. If you had a folder with file1.csv, file2.csv, etc., up to 9, then you could use file?.csv to refer to all of them but this would not pick up file10.csv.

Another special character we’ve already seen is the curly brace, {}. Whenever you have a common substring in a series of commands using curly braces tells the command line to expand what’s in them automatically. In an example above, this is used on 1 to 5. But it can also be used in, for example, file names:

cp /path/to/project/{foo,bar,baz}.csv /newpath

would copy the csv files called foo, bar, and baz to the directory /newpath. Similarly,

touch {a..c}{.csv,.txt}

would create the files a.csv, a.txt, b.csv, b.txt, c.csv, and c.txt.

Scripting#

For tasks that will be repeated, it’s more reproducible and reliable to put your terminal commands into a script than executing them from memory each time—not to mention a lot easier! Because the command line has its own language, we can create scripts that execute commands. There are some differences between bash and zsh but we’ll try and keep the guidelines general.

Create a script called hello_world.sh. Inside it, write:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Hello World!"

The first line is called a shebang and it indicates what programme to run the commands below with (sh means any Bash-compatible shell). The # character also indicates a comment. The second part will print out a string to the screen. Now, depending on whether you’re using bash or zsh, run

bash hello_world.sh

# or

zsh hello_world.sh

Let’s see a more complex example:

#!/bin/bash

echo "Starting program at $(date)"

echo "Running program $0 with $# arguments

which produces

Starting program at Thu 25 Mar 2021 21:23:22 GMT

Running program hello_world.sh with 0 arguments

Notice that using "$(command)" inserted the output of the command into the text string. To assign variables in bash and zsh scripts, use the syntax foo=bar (no spaces) and access the value of the variable with $foo.

Strings can be defined with ' and " delimiters, but they are not equivalent. Strings delimited with ' are literal strings and will not substitute variable values whereas " delimited strings will.

Bash and zsh have a couple of unusual features as compared with other languages because of what they are used for. One of those are the special variables that come pre-defined, one of which we saw in the example above. Here is a list of some of the main ones:

$0- Name of the script$1to$9- Arguments to the script (ordered by the numbers)$@- All the arguments$#- Number of arguments!!- Entire last command, including arguments

You can find more of these special variables here.

Useful command line tools#

pandoc is absolutely brilliant: if you need to convert files containing text from one format to another, it really is a swiss-army knife. There isn’t space here to list the ridiculous number of documents it can convert between, but, importantly, it can translate back and forth between all of the following: markdown, \(\LaTeX\), Microsoft Word’s docx, OpenOffice’s ODT, HTML, and Jupyter Notebook.

It can also write from any of those formats (and more) in one direction to PDF, Microsoft Powerpoint, and \(\LaTeX\) Beamer.

To use pandoc, install it following the instructions on the website and then call it like this:

pandoc mydoc.tex -o mydoc.docx

This is an example where the input is a .tex document and the output, -o, is a Microsoft Word docx file.

You can get quite fancy with pandoc, for example you can translate a whole book’s worth of latex into a Word doc complete with a Word style, a bibliography via biblatex, equations, and figures. Nothing can save Word from being painful to use, but pandoc certainly helps.

exa is an upgrade on the ls command. It is designed to be an improved file lister with more features and better defaults. It uses colours to distinguish file types and metadata. Follow the instructions on the website to install it on your operating system. To replace ls with exa, you can use a terminal alias. There’s a good guide available here.

nano is a built-in text editor that runs within the terminal. This can be really useful if you’re working on the cloud (but it’s not got the rich features of a GUI-based text editor like VS Code). To open a file using nano, the command is nano file.txt. Nano displays instructions on how to navigate when it loads up but exiting is the hardest part: when you’re done, hit Ctrl+X, then y to save, and then enter to exit.

wget is a command-line utility for downloading files from the internet. It’s very simple to use, the syntax is just wget [options] [url]. For example, to download the starwars csv file used in this book, the command is

wget https://github.com/aeturrell/coding-for-economists/blob/main/data/starwars.csv

htop is a tool that lets you see what processes are running on your computer at any time (across individual processors), and how much memory you are using up. To install it on a Mac, you can use brew install htop if you use homebrew. Otherwise you can compile it from source after downloading it from the website. To use it, simply type htop on the command line.

parallel is a tool for executing jobs in parallel using one or more processors on your computer. A job can be a single command or a small script that has to be run for each of the lines in the input. The typical input is a list of files, a list of URLs, or similar. It’s useful in coding when you have a so-called embarrassingly parallel job that can be perfectly and evenly split into sub-operations. You may need to install it using brew install parallel (Mac) or apt-get install parallel (most Linux distributions).

Using all of the processors available on your computer, you can launch the jobs in parallel batches of as many as you like. For example, if you had a python script called print_num.py that prints the number it is given as an input via sys.argv:

import sys

import time

if __name__ == "__main__":

time.sleep(6)

print(f'Input settings: {sys.argv}')

Using parallel, we would launch the script 50 times over in batches of 10 using

seq 50 | parallel -j 10 python print_num.py

And you would see

Input settings: ['print_num.py', '1']

Input settings: ['print_num.py', '2']

...

etc.

ncdu is a disk usage analyser. It reports, interactively and via the terminal, how much space in a folder is taking up. You can also use return to enter a folder and explore sub-folders. This is especially useful when using a remote computer that you can’t view via a graphical user interface (GUI).

ffmpeg is a command line tool that aims to “decode, encode, transcode, mux, demux, stream, filter and play pretty much anything that humans and machines have created. It supports the most obscure ancient formats up to the cutting edge.” Look at the documentation for all of the uses.

yank reads input from stdin (what you see in the terminal) and displays a selection interface that allows a field to be selected and copied to the clipboard. A typical use case would be to copy and paste a file name that you’ve found from using the ls command. For example, running ls -lah | yank in a directory brings up a list of permissions, sizes, users, dates modified, and names of files. You can then navigate to the filename you want with the keyboard, hit return, and have that file name in the clipboard ready to paste into your next terminal command. There’s a nice demo here.

For more on the command line, see The Art of the Command Line. In terms of other commands, you might like to check out patch, sed, and awk.

Review#

This brief introduction to the command line, should have made you feel comfortable with: opening terminal windows; using built-in commands to change directories, rename files, and list files; using Python on the command line; scripting terminal commands; and using installed command line tools such as pandoc.