Code in Style#

In this chapter, you’ll learn some of the easiest and most impactful tips for better coding. This chapter has benefitted from the Clean Code In Python guide by Nik Tomazic and the UK Government Statistical Service’s Quality Assurance of Code for Analysis and Research guidance (which is well worth checking out).

As this is the bare bones of best practice coding, we won’t cover some very important but more complex topics, such as reproducibility, testing, and version control, here.

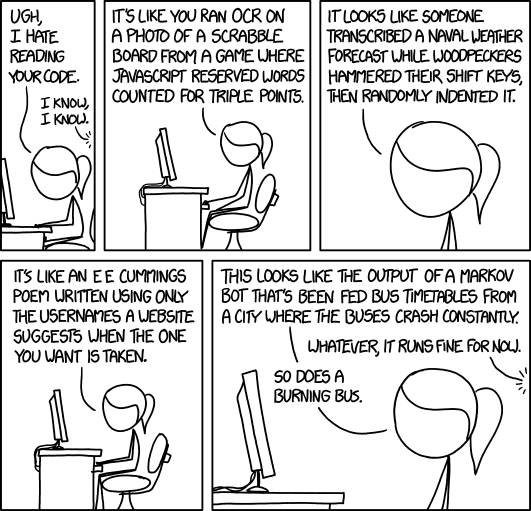

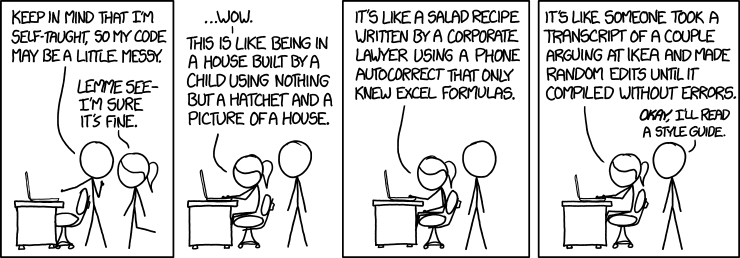

There are many ways to write equally valid code and, over the years, software developers have worked out ways that help to make writing, using, debugging, and reading code more fun and certainly more efficient. Following these best practice tips will save you hours and hours of time.

Remember, most of the time, you are going to be writing code that someone else will read (most probably it will be future you), or that you’ll need to run again. So you may think that by cutting out some of these practices that you’ll save time, but it depends how heavily you discount your future time! It’s almost always worth it to follow best practices.

If you follow the guidelines in this chapter you will find that your code will be:

easier to understand

more efficient

easier to maintain, scale, debug, and refactor

How to Code in Style#

The first thing to think about is code style, ie the way you write equivalent valid code.

Don’t worry if this all seems like a lot to take in though, because in Shortcuts to Better Coding we’ll find out how to get the computer to apply style to your code automatically.

Python has a whole set of conventions about good style called ‘PEP8’, which it’s worth taking a quick look at. It includes advice like indentation should always be 4 spaces (not tabs) per level and that you should surround top-level function and class definitions with two blank lines.

Most programming languages have a style guide, or at least some conventions! PEP8 is not the only Python style guide around: another popular one is the Google style guide. But PEP8 is the most popular.

Learning all of the PEP8 conventions would be tedious beyond belief. The good news is that a combination of packages and Visual Studio Code will do a lot of them for you. Packages can re-style and even re-write your code automatically (more on that in Chapter on Shortcuts to Better Coding).

What’s in a name?#

First, names matter. Use meaningful names for variables, functions, or whatever it is you’re naming. Avoid abbreviations that you understand now but which will be unclear to others, or future you. For example, use real_wage_hourly over re_wg_ph. I know it’s tempting to use temp but you’ll feel silly later when you can’t for the life of you remember what temp does or is. A good trick when naming booleans (variables that are either true or false) is to use is followed by what the boolean variable refers to, for example is_married.

As well as this general tip, Python has conventions on naming different kinds of variables. The naming convention for almost all objects is lower case separated by underscores, e.g. a_variable=10 or ‘this_is_a_script.py’. This style of naming is also known as snake case. There are different naming conventions though—Allison Horst made this fantastic cartoon of the different conventions that are in use.

Different naming conventions. Artwork by @allison_horst.

Different naming conventions. Artwork by @allison_horst.

There are three exceptions to the snake case convention in Python: classes, which should be in camel case, eg ThisIsAClass; constants, which are in capital snake case, eg THIS_IS_A_CONSTANT; and packages, which are typically without spaces or underscores and are lowercase thisisapackage.

For some quick shortcuts to re-naming columns in pandas dataframes or string variables, try the unicode-friendly slugify library or the clean_columns() function from the skimpy library.

The better named your variables, the clearer your code will be–and the fewer comments you will need to write!

In summary:

use descriptive variable names that reveal your intention, eg

days_since_treatmentavoid using ambiguous abbreviations in names, eg use

real_wage_hourlyoverrw_phalways use the same vocabulary, eg don’t switch from

worker_typetoemployee_typeavoid ‘magic numbers’, eg numbers in your code that set a key parameter. Set these as named constants instead. Here’s an example:

import random # This is bad def roll(): return random.randint(0, 36) # magic number! # This is good MAX_INT_VALUE = 36 def roll(): return random.randint(0, MAX_INT_VALUE)

use verbs for function names, eg

get_regression()use consistent verbs for function names, don’t use

get_score()andgrab_results()(instead useget()for both)variable names should be snake_case and all lowercase, eg

first_nameclass names should be CamelCase, eg

MyClassfunction names should be snake_case and all lowercase, eg

quick_sort()constants should be snake_case and all uppercase, eg

PI = 3.14159modules should have short, snake_case names and all lowercase, eg

pandassingle quotes and double quotes are equivalent so pick one and be consistent—most automatic formatters prefer

"

Whitespace#

Surrounding bits of code with whitespace can significantly enhance readability. One such convention is that functions should have two blank lines following their last line. Another is that assignments are separated by spaces

this_is_a_var = 5

whereas keyword arguments in functions do not have spaces

def function(input_one, input_two=5):

return input_one

Another convention is that a space appears after a ,, for example in the definition of a list we would have

list_var = [1, 2, 3, 4]

rather than

list_var = [1,2,3,4]

# or

list_var = [1 , 2 , 3 , 4]

There are packages that can re-organise your whitespace for you; these are featured in the Chapter on Shortcuts to Better Coding.

In summary,

indent using 4 spaces (spaces are preferred over tabs)

lines should not be longer than 79 characters

avoid multiple statements on the same line

top-level function and class definitions are surrounded with two blank lines

method definitions inside a class are surrounded by a single blank line

imports should be on separate lines

Line width and line continuation#

For quite arbitrary historical reasons, PEP8 also suggests 79 characters for each line of code. Some find this too restrictive, especially with the advent of wider monitors. But it is good to split up very long lines. Anything that is contained in parenthesis can be split into multiple lines like so:

def function(input_one, input_two,

input_three, input_four):

result = (input_one,

+ input_two,

+ input_three,

+ input_four)

return result

Again, automatic formatters, which we’ll meet in the Shortcuts to Better Coding Chapter, will try and break up long lines for you.

Principles of Clean Code#

While automation can help apply style, it can’t help you write clean code. Clean code is a set of rules and principles that helps to keep your code readable, maintainable, and extendable. Writing code is easy; writing clean code is hard! However, if you follow these principles, you won’t go far wrong.

Do not repeat yourself (DRY)#

The DRY principle is ‘Every piece of knowledge or logic must have a single, unambiguous representation within a system.’ Divide your code into re-usable pieces that you can call when and where you want. Don’t write lengthy methods, but divide logic up into clearly differentiated chunks.

This saves having to repeat code, having no idea whether it’s this or that version of the same function doing the work, and will help your debugging efforts no end.

Some practical ways to apply DRY in practice are to use functions, to put functions or code that needs to be executed multiple times by multiple different scripts into another script (eg called text_cleaning_utilities.py) and then import it, and to think carefully if another way of writing your code would be more concise (yet still readable).

Tip

If you’re using Visual Studio Code, you can automatically send code into a function by right-clicking on code and using the ‘Extract to method’ option.

KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid)#

Most systems work best if they are kept simple, rather than made complicated. This is a rule that says you should avoid unnecessary complexity. If your code is complex, it will only make it harder for you to understand what you did when you come back to it later.

SoC (Separation of Concerns) / Make it Modular#

Depending on your project, it’s usually best to not have a single file that does everything. If you split your code into separate, independent modules it will be easier to read, debug, test, and use. You can check the basics of coding chapter to see how to create and import functions from other scripts. But even within a script, you can still make your code modular by defining functions that have clear inputs and outputs.

A good rule of thumb is that if a code that achieves one end goes longer than about 30 lines, it should probably go into a function. Scripts longer than about 500 lines are ripe for splitting up too.

Relatedly, do not have a single function that tries to do everything. Functions should have limits too; they should do approximately one thing. If you’re naming a function and you have to use ‘and’ in the name then it’s probably worth splitting it into two functions.

Functions should have no ‘side effects’ either; that is, they shouldn’t only take in value(s), and output value(s) via a return statement. They shouldn’t modify global variables or make other changes.

Another good rule of thumb is that each function shouldn’t have lots of separate arguments.

A final tip for modularity and the creation of functions is that you shouldn’t use ‘flags’ in functions (aka boolean conditions). Here’s an example:

# This is bad

def transform(text, uppercase):

if uppercase:

return text.upper()

else:

return text.lower()

# This is good

def uppercase(text):

return text.upper()

def lowercase(text):

return text.lower()

Code Comments#

Code comments (extra information that is not executed when the code is run) can be added by a preceding hash character # This is a comment. Use code comments to provide extra contextual information that isn’t conveyed by function and variable names.

Actually, well-written code needs fewer comments because you make what’s going on more evident to the reader. And it’s tempting not to update comments even when code changes. So do comment, but see if you can make the code tell its own story first.

Also, avoid “noise” comments that tell you what you already know from just looking at the code.

Finally, functions come with their own special type of comments called a doc string. Here’s an example that tells us all about the functions inputs and outputs, including the type of input and output (here a dataframe, also known as pd.DataFrame).

def round_dataframe(df: pd.DataFrame) -> pd.DataFrame:

"""Rounds numeric columns in dataframe to 2 s.f.

Args:

df (pd.DataFrame): Input dataframe

Returns:

pd.DataFrame: Dataframe with numbers rounded to 2 s.f.

"""

for col in df.select_dtypes("number"):

df[col] = df[col].apply(lambda x: float(f'{float(f"{x:.2g}"):g}'))

return df

Code Review#

Perform code reviews: give what you’ve done to a colleague and ask them to go through it line-by-line to check it works as intended. If they do this properly and don’t find any mistakes or issues then I’d be very surprised. Return the favour to magically become a better coder yourself.

Don’t prematurely optimise for speed#

Make code correct and readable first, and fast second. You can waste a lot of time optimising only to find that either the bottleneck is not where you thought it was, or that you change your mind about what process needs to be done.

Use interoperable file formats#

We’ll talk much more about data in an upcoming chapter. For now, some basic pointers for the most common form of data: tabular data that’s arranged in columns and rows.

First: do not store your data in Excel file formats. Ever. First, it’s not an open format, it’s proprietary, even if you can open it with many open source tools. Second, more importantly, Excel can do bad things like changing the underlying values in your dataset (dates and booleans), and it tempts other users to start slotting Excel code around the data. This is bad - best practice is to separate code and data. Code hidden in Excel cells is not very transparent or auditable.

If you want examples of what can go wrong using Excel, look no further than the famous Reinhart and Rogoff Excel error, where they didn’t select all cells (it’s harder to make this kind of mistake with real programming languages, though of course not impossible), the time when a first-year law associate added an extra 179 contracts to an agreement to buy Lehman Brothers assets, or when the UK under-counted the number of coronavirus cases by 16,000 because their Excel spreadsheet wasn’t big enough. In programming, the dataset limitation is the size of your computer’s hard drive (and even then, you can jump onto the cloud).

In the majority of cases, the best data file format for your project is CSV–certainly for outputting final results. Everyone can open a CSV file, no matter what analytical tool or operating system they are using. As a storage format, it’s unlikely to change. Without going into the mire of different encodings, save it with the UTF-8 encoding (note that this is not the default encoding in Windows).

Do not use Stata’s .dta format for storing data, especially long term. For one thing, the format changes with the version of Stata. You do not want your data to depend on what version of software you’re using! Second, it isn’t very interoperable across tools (although you can use pd.read_stata() in Python). Third, it is not very efficient in the way that it uses disk space.

Although open source and compressed, I also don’t recommend the statistical language R’s RDS format or Python’s pickle format, because neither are easily accessible from other tools. These are okay for intermediate data within a project that won’t persist, but you could also use parquet for that, which is cross-platform.

And if you’re working with big data, I strongly recommend the parquet file format. In most programming languages, it’s blazing fast for input/output and packs down to a very efficient size. For example, a file saved in parquet might be 10 times smaller than the same .dta file; in tests, a 114 Mb parquet file was a whopping 4.68 GB in R’s RDS format. If you’re using cloud or have a small laptop, these space-savings add up. Better yet, parquet is available across a wide range of tools and languages including Python, R, Ruby, C++, Java, and Go. (Worth saying that parquet won’t always be the right choice, but it’s a great default for big data.)

Use relative filepaths#

A path, or filepath, is a slash-separated list of directory names followed by either a directory name or a file name. You’ll use them to read data into code, for example using df = pd.read_csv('path/to/data.csv'). A directory is the same as a folder. On Unix based systems (Mac and Linux), these paths use forward slashes:

/Users/yourname/Documents/projects/file.csv

On Windows, which insists on being different, the slashes go the other way:

C:\Documents\projects\file.csv

These are absolute paths, that is they give the full information to go from a disk to the file. These are okay on your computer, but they are useless for replicability or for working with co-authors. It’s much better in that case to use relative paths, where the path to a file is defined relative to a project folder. For example,

project_folder/data/raw/file.csv

Then, we use the convention that code executed for a project should have the project folder as its root directory, and any paths are relative to it. So to open file.csv using pandas, you would use

import pandas as pd

df = pd.read_csv('data/raw/file.csv')

This works great on Mac and Linux, but it’s not going to work on Windows; Windows uses backwards slashes, and back slashes unfortunately tend to do other things in programming too. To ensure relative paths work across operating systems, the best way is to wrap the file path in a call to the Path() method in the pathlib module:

from pathlib import Path

import pandas as pd

path_to_data = Path('data/raw/file.csv')

df = pd.read_csv(path_to_data)

pathlib will translate the relative path you have entered into whatever the local operating system needs.

Setting up Visual Studio Code so that Python interactive windows and terminals start in the current folder, typically your project’s root directory, makes it easier to use relative filepaths.

Start interactive windows and terminals within your project directory

In Visual Studio Code, you can ensure that the interactive window starts in the root directory of your project by setting “Jupyter: Notebook File Root” to ${workspaceFolder} in the Settings menu. For the integrated command line, change “Terminal › Integrated: Cwd” to ${workspaceFolder} too.

Rubber duck your problems#

Rubber duck debugging is a method of fixing code that isn’t working as intended by, err, talking to a rubber duck. Something about describing your problem out loud and in detail can suddenly illuminate the issue to you and your plastic waterfowl friend.

🦆

The Zen of Python#

For a more poetic take on how to code, import this in your Python session.

import this

The Zen of Python, by Tim Peters

Beautiful is better than ugly.

Explicit is better than implicit.

Simple is better than complex.

Complex is better than complicated.

Flat is better than nested.

Sparse is better than dense.

Readability counts.

Special cases aren't special enough to break the rules.

Although practicality beats purity.

Errors should never pass silently.

Unless explicitly silenced.

In the face of ambiguity, refuse the temptation to guess.

There should be one-- and preferably only one --obvious way to do it.

Although that way may not be obvious at first unless you're Dutch.

Now is better than never.

Although never is often better than *right* now.

If the implementation is hard to explain, it's a bad idea.

If the implementation is easy to explain, it may be a good idea.

Namespaces are one honking great idea -- let's do more of those!

Advanced Coding Tips#

Warning

If you are just learning to code you should feel free to skip this section for now.

There are many other coding tips that are useful but that make use of concepts or tools that we haven’t met yet. To be comprehensive, they are included here—but we’ll be seeing most of them in the other coding chapters.

Version Control#

Control versions of your code using Git, which is the standard for research, industry, and everyone on planet Earth.

Code should be committed regularly, preferably when a discrete unit of work has been completed.

Continuous integration, for example using tools such as GitHub Actions, should be used to ensure that each change is integrated into the workflow smoothly.

Configuration#

Credentials and other secrets are not written in code but are configured as environment variables.

Configuration as applied to code or simulations is written as code, but is clearly separated from code used for analysis.

The configuration used to generate particular outputs, releases and publications is recorded.

If appropriate, multiple configuration files are used and interchangeable depending on system/local/user.

Environments#

Code environments are reproducible and development is done within a consistent code environment.

Project management#

The roles and responsibilities of team members are clearly defined.

An issue tracker (e.g GitHub Project, Trello, or Jira) is used to record development tasks.

Testing#

Core functionality is unit tested as code.

Code based tests are run regularly and before each commit (for example using pre-commit).

Bug fixes include implementing new unit tests to ensure that the same bug does not reoccur.

Tests are automatically run and recorded using continuous integration.

The whole process is tested from start to finish using one or more realistic end-to-end tests.

Test code is clean an readable.

Review#

From this chapter, you should remember to

✅ know what a code style is;

✅ not repeat yourself;

✅ be consistent with your naming convention;

✅ write modular, well-documented code;

✅ use interoperable file formats;

✅ use relative file paths; and

✅ stay zen!